Chronic Inflammation & the Immune System

My cookbook, The Plant-Based Anti-Inflammatory Cookbook, provides more information on inflammation, a list of “anti-inflammatory superstars” (foods you can get at the grocery store that help fight inflammation), and dozens of recipes using these superstars. Check out more details about the cookbook, and links to sites where you can buy it, by clicking here.

“Chronic inflammation.” “Metainflammation.” “Inflammaging.” They sound scary. How do you know if you’re suffering from one or more of them? What’s going on in your body when it’s “inflamed”? And how can you adjust your diet to prevent or moderate inflammation?

These very important questions can’t be answered in a single blog post. I’ll be tackling them in a series of posts about chronic inflammation. In this first post in the series, I’ll provide a critical foundation to understanding chronic, meta-, and age-related inflammation.

Lots of articles I’ve seen about chronic inflammation jump right into symptoms or treatments. I believe it’s important to review the human immune system, since it’s the immune system that creates inflammation—both the good kind and the not-so-good kind.

Purpose of the immune system

At any given moment, foreign organisms and matter are entering our bodies. Maybe we just inhaled air that contained pollen, pollution, second-hand smoke, or an airborne virus. Perhaps we just rubbed our eyes after touching a surface recently fingered by someone with a cold. Or we cut ourselves with the tip of a kitchen knife. Or we ate a sandwich with vegetables and spreads, each of them carrying microscopic travelers that make it into our gut. As much as we might perceive our bodies as sealed off from the world and consider ourselves careful about germs, in actuality the world gets into our bodies all the time and in many different ways.

The purpose of our immune system is to monitor what enters our bodies, deal with harmful invaders like bacteria, viruses, and other potential pathogens, and start the healing process. The extensive immune system in each of our bodies mobilizes itself to identify, attack, kill, and clean up germs, toxins, and other irregularities it finds.

Parts of the immune system

When we study body systems—like the digestive, cardiovascular, and reproductive systems—we tend to focus on the major organs—heart, lungs, stomach, uterus, and the like. That’s where the action usually is. But the major actors of the immune system are not organs, but the billions of immune cells and trillions of proteins positioned all over our body, constantly on the alert and ready to be activated at a nanosecond’s notice. Think of them as the baddest Neighborhood Watch network ever. The other players in the immune system are, for the most part, enablers of the immune cells and proteins—birthing them, incubating them, and providing storage, meeting places, and pathways for the cells and proteins to do their work.

Immune cells

Immune cells—also called leukocytes or white blood cells—are the most critical players in the immune system. There are thousands of different immune cell types, but they can be grouped into two main types (see diagram). One type—called myeloid cells—act quickly when they detect infections, toxins, or abnormalities. They send signals to other cells to mount a quick response to the problem. A few of the better known cell types in this group are neutrophils, mast cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells.

The second group of immune cells is called lymphoid cells and includes B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells. They are able to preserve the memory of previous infections. They can preserve the imprint of pathogens they’re exposed to and are ready to attack the next time they encounter them.

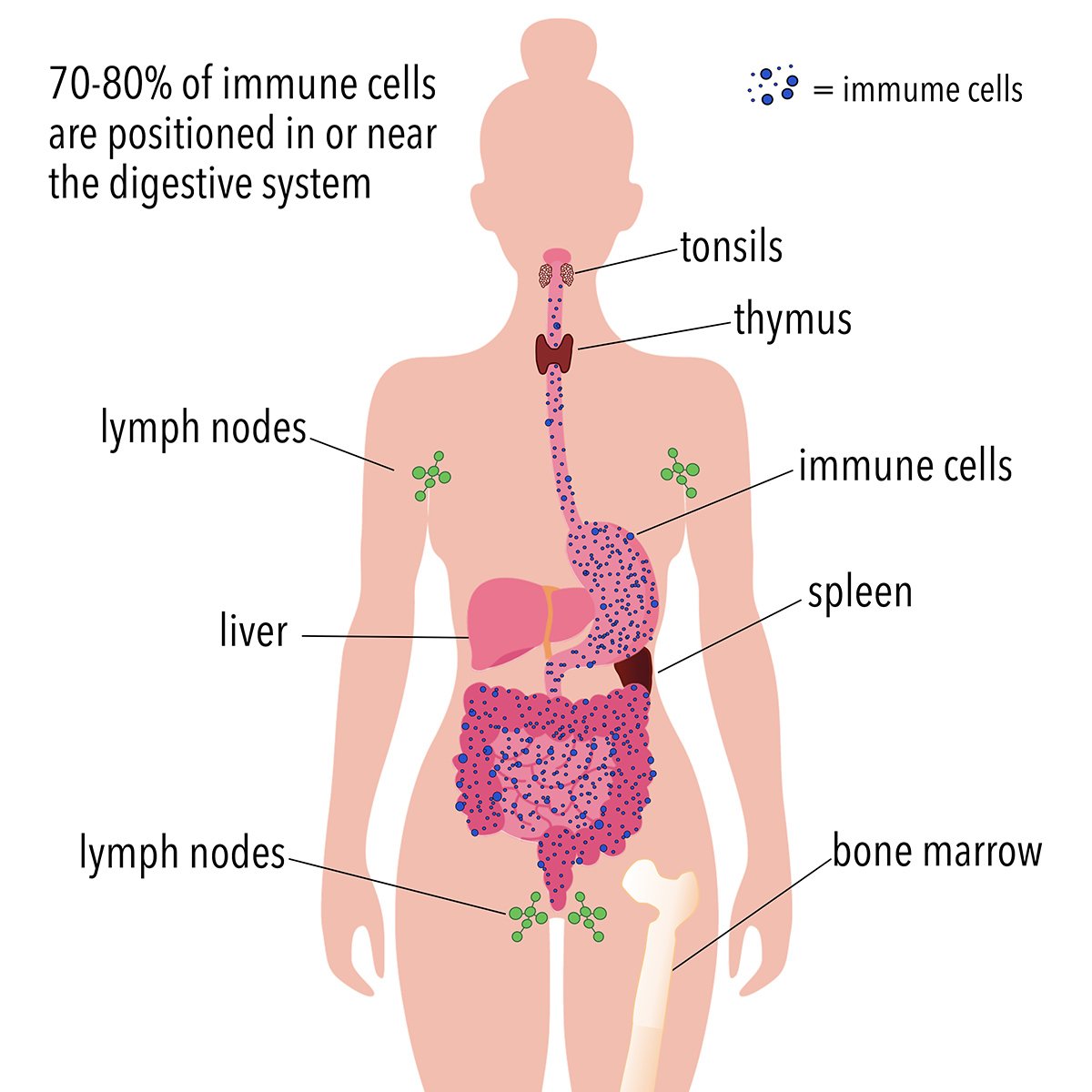

Immune cells travel through the body—in the blood stream and the lymph system (see more on this below). But contrary to the notion that immune cells are constantly swimming through our veins or lymphatic vessels, most immune cells are stationed in tissues or mucous layers, especially where germs and toxins are liable to enter the body. Researchers estimate that 70-80% of immune cells are positioned in or near the digestive system (see diagram), and many others reside in the skin, locations where the outer world is most likely to enter the body.

Immune system proteins

Proteins are not cells (which can metabolize nutrients, provide their own energy, and replicate themselves) but rather molecules made up of amino acids. Among the many types of proteins in the immune system, the most numerous are cytokines. Cytokines serve as messengers for the immune system. In fact, in some situations, immune cells secrete cytokines, thereby sending signals to other immune cells that their help is needed to address a situation.

Other parts of the immune system

The organs and other parts of the immune system play supporting roles to the trillions of immune cells and proteins that do the actual work of the immune system.

Liver

The liver produces immune-system proteins and hosts immune cells that ingest bacteria from the blood.

Spleen

The spleen is a site where immune cells filter blood and where immune cells adapt to invading germs.

Thymus

The thymus provides an environment where T cells mature.

Bone marrow

Immune cells begin their development from stem cells in the bone marrow.

Tonsils

Tonsils are nodes in the back of the mouth containing immune cells that help filter out bacteria and other germs that enter through the mouth.

Lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels

The lymph system provides storage nodes for immune cells and a dedicated pathway throughout the body for use by immune cells.

When the immune system overreacts

The immune system, with its thousands of types of immune cells, trillions of signaling proteins, and dedicated waystations and highways, is terribly sophisticated, but also terribly sensitive. The ideal state for the immune system is a balance between tolerating benign substances while neutralizing and removing dangerous germs and toxins, with pinpoint accuracy in distinguishing one from the other. Scientists call this ideal state “immune homeostasis.”

Unfortunately, there are times when the immune system reacts to phenomena in the body that it considers irregular, but its reactions don’t help and often make things worse. Allergies and autoimmune diseases are instances of misguided reactions – to harmless substances like pollen, causing allergic reactions, or to our own tissues, as in arthritis.

Other phenomena that the immune system reacts to were rare or non-existent when humans evolved over millennia. For example, obesity was rare in the environments of scarcity in human prehistory. We now know that enlarged fat cells release pro-inflammatory compounds that activate the immune system, causing immune cells to work hard to rid the body of those secretions, which just keep on coming from the growing fat cells.

Deposits of cholesterol on the coronary arteries were also rare, as we know from medical records of people who live in rural or island areas where the plant-rich diets are most similar to what prehistoric humans ate. We now know that in many people with cholesterol deposits, immune cells work to rid the arterial walls of the cholesterol, leading to swollen, inflamed arteries and sometimes even a dislodging of the deposit, which can lead to a stroke or heart attack.

The immune system also interacts with “good” and “bad” bacteria in the gut as well as oxidative stress throughout the body. Because of our modern diet, industrial toxins, relatively recent vices like smoking, and tendencies toward excess weight, humans are often out of sync with our immune systems, which evolved in a different time, and we pay highly for it.

Conclusion

My goal is to get into better sync with my immune system and help others do the same – especially to eat in ways that keep the immune system from inflaming our bodies. Future blogs will go into more detail about how the immune system can inflame the body and create an environment for disease to thrive. We’ll also cover the type of diet and foods that can help avoid the conditions that make the immune system attack. There is hope, and a well-balanced immune system is worth the effort.

For further reading

If you want to know more about the immune system, I recommend the online Encyclopedia Britannica article on the immune system. For those who want to go further and delve into the (fascinating) history of how scientists figured out the immune system, I highly recommend Shilpa Ravella’s A Silent Fire: The Story of Inflammation, Diet, and Disease.